Study of corner

Anthropologist, speculative feminist and author Anna Tsing says, ‘telling stories of landscape requires getting to know the inhabitants of the landscape, human and not human”.[1] She advocates for observation and fieldwork, practicing many different ways of knowing including histories; written and oral, utilising technology, science and the arts, following sensory and materially-led curiosities, and learning the histories of disturbances, human and natural. She calls this a practice of “noticing”.

1959

The area where I live used to be covered in Kauri. This was before the trees were harvested and logs were dragged down to the beach to be put on barges. It was also a sanctuary for birds, many of the street-names are bird species. Sadly the bird of my street-name does not exist in body, in this place.

1959

1996

2017

The corner

Made by a boundary line set over 50 years ago when the land was subdivided into 4 human dwellings that straddled a creek, and were sold off separately. Running through the corner of this slice of utopia is a 100 year overland flow path. In winter the ground is really wet. In the drier seasons a game of bat-down can be played on its bumpy pitch.

The corner from my bedroom window

At the centre line is the Taiorahi Creek, running thin within narrowed boulder-clad walls[2]. When the heavy rain comes the water seeps, splashes and rises, as it looks for an outlet on its way to the ocean – hence the overflow path. The water folds over broken branches, stones and wayward root systems, its voice-box somewhat strangled.

Taiorahi creek with stone-clad wall

The creek running to meet the ocean

There is a wooden fence that runs adjacent to the creek inside this flow path, set back with space below and between for an overflow of water to spill though. It sits on our boundary and was there when we arrived. We face the fence’s mossy spine and vertical trusses, not its flat face. This fence is magnificent! – wet with life, stained with pollen and fungi, spider webs bandage its joints and manage the marching insects. Nearby tree-roots, along with the pushing and shoving of the vegetational growth on the fence’s creek side, have warped its fudgy foundations. The fence speaks in wah wah tones, catching and tossing the wind with its gnarly knuckles.

Disturbance

A disturbance is an opening for action, says Tsing. It realigns possibilities for transformative encounter.[5] My own corner of this world has experienced and is experiencing natural and human disturbances all the time.

Tsing says disturbance matters in relation to how we live, so deciding what counts as disturbance is always a matter of point of view. “Disturbance refers to an open-ended range of unsettling phenomena”.[4] I think about my perspective, as human, as care-taker.

- Easterly storm takes out large Snag[3] from corner of property. Tree goes crashing through wing of fence and into the creek. Circa 2018.

- Human Disturbance: Trunk was blocking water flow, and so log was removed from creek. Fence was broken up and taken away.

- Natural disturbance: Another easterly storm takes out young, yet seemingly fragile Pohutukawa tree. Circa 2020

- Human Disturbance: Site cleared up – intention to restore. Broken trunk cut smooth by arborist using chainsaw.

I remember the sound of the storm, the shaking of the house, the whirring of the wind that thrust at the window panes, and the snapping of the tree falling into the arms of the fence, tearing the treated wood off its nailed frame. I felt the disturbance in my body, does this mean I’m part of the assemblage? and I feel for the tree, and I feel for the fence; heaving, wounded, wingless.

I think about all the other feeling feelers in this open-ended assemblage. There must have been numerous disturbances that have gone unnoticed, by me, in this corner. Just today I felt the land moving and the house shaking because of the thrusting power of a home-demolition in action, further down the street. I think about the impact of the changes I make to this environment in my desire for somewhere ‘nice’ to live, and what that means.

When the trees fell there was more light, increased growth, more ground cover, and more space for birds and other critters to move. I felt a different kind of connection to this place, part of its curiosity — is this the beginning of resurgence in this assemblage, and what role do I play?

I move in close, to notice

Light falls directly onto the exposed heartwood belly of a young Pohutukawa stump. This ethereal sight is what drew my attention initially.

So-called weeds cloak the stump, surrounded by a collection of plant-life from around the globe, each reaching upwards towards the sun.

I use my new App: Picture This, which helps to determine and name unknown plant-life …

Moving around the stump, this intrepid coastal Pohutukawa tree, still holds steadfast with its tentacle-like roots tunnelling under the remaining fence-line, down the wall of the creek. This tree, although beautiful, and offering rich nectar for the birds, has an invasive quality and ability to displace other natives. It is a glorious coastal creature but when planted inland creeping roots can destroy sewer systems and infrastructure.

To the West of the stump is a Sliver Fern-tree Punga, with glorious green fronds that arch over to greet this new light. The light in relationship with this patch creates amazing colours.

Skeleton leaves at various degrees of decay are wedged amongst the growth, they are so delicate and skin-like. This makes me think about the bare Pohutukawa stump, exposed without its protective epidermis.

Hanging over ‘the corner’ is our neighbour’s Royal Star Magnolia tree, native to Japan. This tree flowers in winter, warming my heart like the pink rosy cheeks of laughing children.

When the wind blows these pink and white petals scatter to the floor like teardrops. From down on the ground I also see daisies, buttercups, and these fluffy white things[6] that bring forth memories of chasing dandelion seeds as a child. On closer inspection the fluff belongs to the Plume albizia tree, part of the wattle family, and considered a weed. The seed pops out from a dangling pod, fluffs up like yellow candy floss, before discolouring and detaching. I sit in the grass and make a daisy chain.

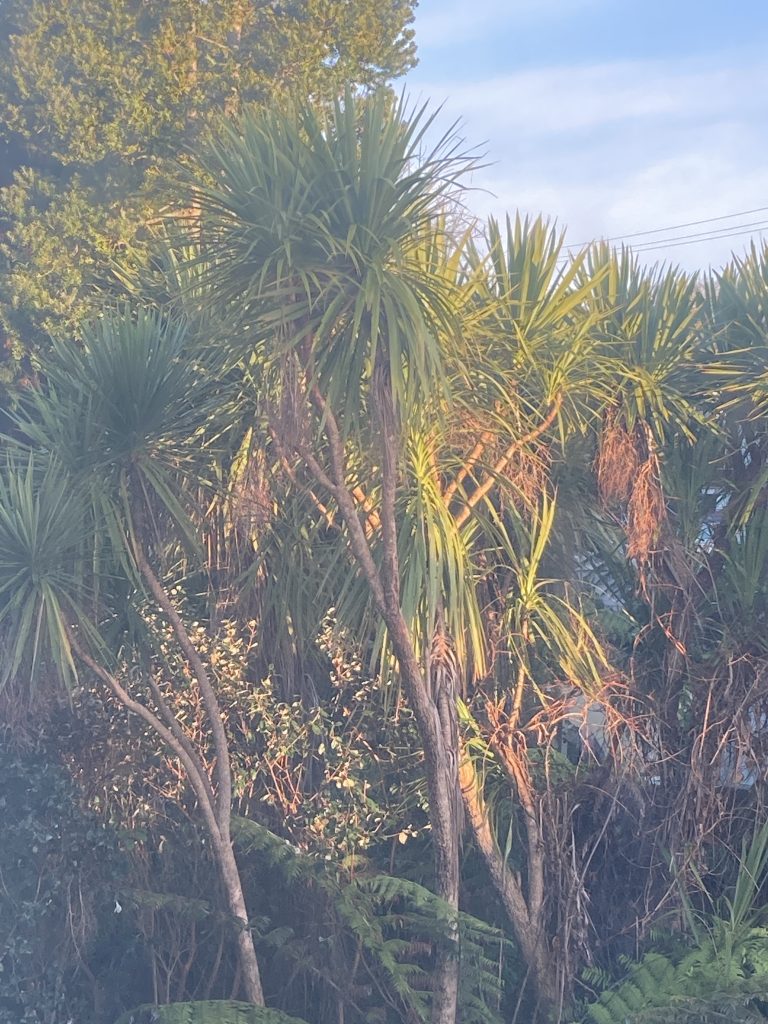

Looking up, I see the cabbage tree shaking it heads like a Truffula tree; “I am the Lorax. I speak for the trees. I speak for the trees for the trees have no tongues.”[7] This makes me think about the notion of a “voice without organs, in which voice is decoupled from its humanist subject and invoked as part of the assemblage … of human and nonhuman agents.”[8] I wonder, is this what Tsing refers to as the polyphonic gathering of voices and rhythms of the assemblage?[9] I imagine Papatūānuku[10] sending out vibrations from deep within its core, quietly orchestrating. I too become quiet and listen for the voices.

I move in closer

I record shadow dances of the grass and growth on canvas, via film and still image.

I become familiar with the tree stump. Its colour changes massively depending on the amount of rain and sun it receives. I make finger and soft pastel rubbings of the heartwood, and play with the paper rubbings through movement, in relationship with the air.

I carefully take measurements of the stump using antibacterial copper wire.

I examine my gumboots and footprints, trying to tread carefully and lightly and stay out of the gluey, boggy bits.

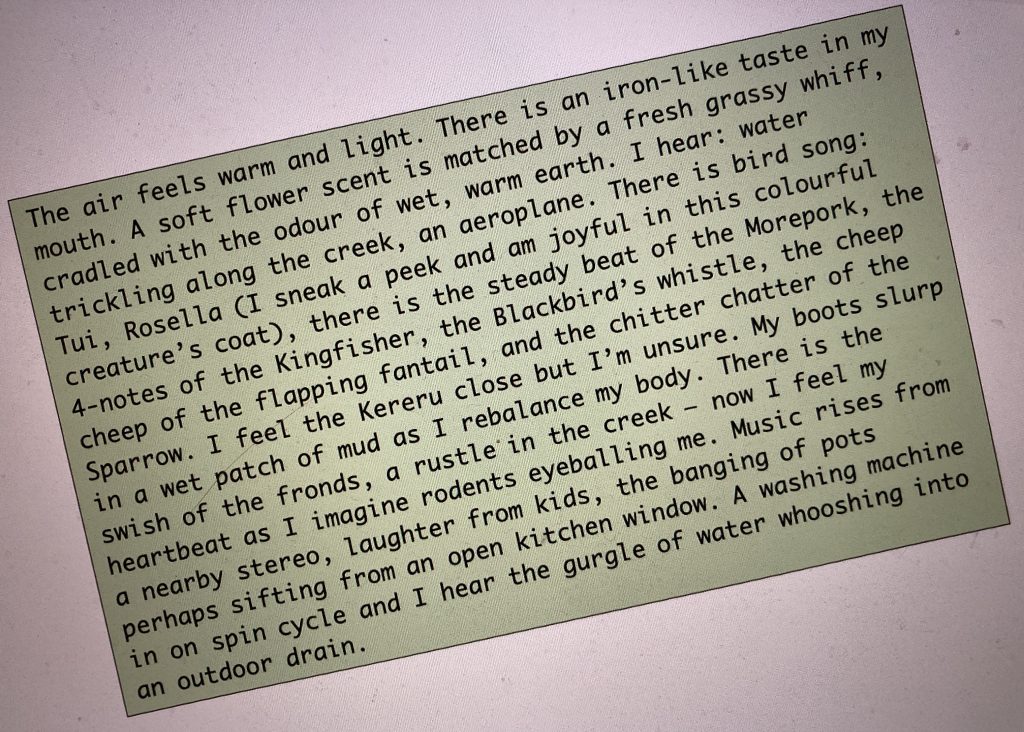

I write what I sense in this place, which seems to change with every encounter.

… and I continue to record the sticky materiality.

[1] Tsing, Anna. The Mushroom at the end of the World, 159.

[2] Auckland Council attempted to strengthen the sides of the creek with boulders, as it was caving in at parts, but they didn’t widen it first and so the retaining wall narrowed the creek, intensifying the flow.

[3] The name for dead trees that are left upright to decompose naturally.

[4] Tsing, 161.

[5] Tsing, 152.

[6] I later find out that this “fluffy thing” is from a semi-toxic weed.

[7] Dr. Seuss, The Lorax.

[8] Mazzei (2013) cited in Monforte, J. and Perez-Samaniego, V. and Smith, B. “Traveling material-semiotic environments of disability, rehabilitation, and physical activity.”, (2020), 5.

[9] Tsing, Mushroom at the end of the World, 24. Discussing the polyphonic assemblage as a gathering of rhythms, as they result from world-making projects, human and not human.

[10] Papatūānuku is mother earth In Māori tradition.

References

Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. The Mushroom at the End of the World. Princeton University Press, 2017.

Monforte, J. and Perez-Samaniego, V. and Smith, B. “Traveling material-semiotic environments of disability, rehabilitation, and physical activity”, (2020). Qualitative health research., 30 (8). pp. 1249-1261.